We Were Warriors

It was at this blissfully innocent and ignorant age, lined up against a padded wall, waiting for my turn “at bat” in kickball that I first heard the chant. Two slaps of the wall pad, followed by a clap, in the approximate rhythm of “We Will Rock You.” Then the words:

We are the Warriors!

Couldn’t be prouder!

If you can’t hear us,

we’ll shout a little louder!

A series of na-na-na-na-nas followed at a steady crescendo.

I was confused. I hadn’t heard this chant before, but it was infectious and before long I had joined in. Nick Samson had been among the first to start the chant. Nick, who I had bonded with kindergarten when we discovered our mutual love for the World Wrestling Federation. The annual Thanksgiving-time Survivor Series pay-per-view event was around the corner, scheduled to feature the four-man team The Warriors—The Ultimate Warrrior, “The Modern Day Warrior” Kerry Von Erich, and The Legion of Doom (formerly known as “The Road Warriors”)—facing off against a crew of bad guys.

It didn’t surprise me that Nick would invent such a chant, or that his boisterous personality would prompt him to break into it in public. It did surprise me the volume of boys and girls who partook, even my budding first crush Pattie, who I couldn’t imagine cheering The Ultimate Warrior as he press slammed a hapless foe.

And yet there she was, red-brown hair and pig tails, four feet tall, screaming along, even giving me a little smile when I caught her eye, in a look I could interpret to be a subtle acknowledgement of the absurdity at the both of us quieter, bookish kids joining the chant.

I’m not sure when the realization hit that the second grade class of Westmoreland Road Elementary was not, in fact, chanting about professional wrestling, but rather in tribute to our schools sports team and broader sports culture. That we were, quite literally, The Warriors—a part of the Whitesboro Central School District, in one of four elementary schools that would feed into a unified junior high four years later, and then into a bigger high school.

I suspect that my classmates, bound to older brothers and sisters, or parents with lingering school pride from their youths, had gone to a football game the preceding Friday night, and come away with this chant in tow. I wouldn’t attend one of these Friday night rituals for another seven years, a high schooler myself, when the games became a backdrop against which to socialize, flirt with girls, and eat soft pretzels.

I came to accept school pride. While I didn’t have any real investment in the school’s sports teams, and wouldn’t call many of the student athletes friends, it still felt abstractly important, when they advanced to a state championship game, that I root for them to win. Moreover, I came to accept the Warrior identity. The school’s logo portrayed a Native American in a headdress—noble and strong. I recognized the na-na-na-nas as an imitation of an Indian war chant. For a mascot, a boy would dress in brown faux-leather regalia with fringe, war paint, and a headdress.

None of this registered as meaningfully problematic to me. There would be the occasional rumbling in the local paper about the mascot and team name appropriating, exploiting, or poking fun at Indian culture. Such concerns were promptly shouted down with cries of it’s a tribute, it’s a tradition, and don’t be so sensitive, ya goddamn pussy!

And though I wouldn’t recognize it until years later, I was indoctrinated in all of this—from the second grade on, even when I associated “The Warriors” not with our football team in white and blue, but rather bare-chested men who wore face paint and spandex. I was surrounded by Warrior culture, and though I was never the most vocal or devout supporter of our school’s athletics, neither did I see a meaningful problem. I joined the chorus of dismissing the overly sensitive, overly PC naysayers who wanted to stir up trouble over the most benign borrowing from Indian culture.

I look back at all of this in my thirties. And, man, that was messed up.

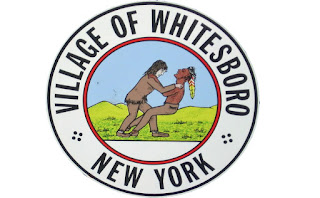

To crystallize the issue, consider the very seal of Whitesboro—the village that lends the school district its name (though the middle school and the administration building—not the high school or any of the elementary schools actually fall within Whitesboro proper). It portrays a white man strangling an Indian. Conquering the primitive savage. Establishing the reign of white people.

I have heard attempts at retconning this image. Claiming it portrays a white man and an Indian in good-spirited competition. That it all comes back to wrestling. But when we look at something so basic as the nomenclature of Whitesboro, I don’t buy it. Boro—a shortening of borough, an area, region, or township. Whites—there’s not an apostrophe, though I think you could argue it’s implied, and thus the borough belongs to white people; alternatively, it establishes the plurality of white people in this village, and the implicit exclusion of people of any other color.

To put a finer point on it, I remember a downtown, outdoor concert that I attended with my father, the summer between sixth and seventh grades. The Orleans—most famous for “Still The One” played on stage. As I transitioned into full-fledged adolescence, I imagined that one of my crushes from school might come to the concert, too, and hold my hand or rest a head on my shoulder.

I remember the tinny sound of the band over an aged speaker system. I remember the smell of beer—it seemed like every adult except for my father had a clear plastic cup of it, drinking sloshing foam over the brim as they danced, offering friends and wives dollar bills for them to buy another cup so they wouldn’t lose their spots in the crowd.

My father, a full-blooded Chinese man, stood out amidst a crowd of white faces. A pot-bellied, red-bearded man in a plain white t-shirt, stained in smudges of tan and brown, dirt and beer, made his way toward him and asked my father, “Are you one of those Indians?”

My father responded that he was Chinese.

The man looked back to his buddies, five or six of them in a row behind us, and made the A-OK sign with his fingers. “He’s a Chinaman.” He turned back to my father. “I was going to ask you how you felt about all this shit at the reservation.”

This shit at the reservation referred to the still-new Turning Stone Casino that a Native American tribe had opened on a reservation in Verona, a half hour drive away. A point of controversy for the gambling culture that it fostered in the area, not to mention that they didn’t charge the state sales tax, which gave them an advantage over local gas stations, restaurants, and retailers—a hot topic of debate in the local media.

I don’t remember what my father said in response—only that he smiled and laughed and kept his answers short. I don’t suspect he shared that he was, himself, a gambler who had taken to visiting the casino on a weekly basis. I suspect he kept things more neutral and to the point. Before long, the bearded man walked away.

I don’t know what would have happened had my father identified himself as Indian, or had he declined to disclose his background. As an eleven-year-old who was prone to both worry and to concocting dramatic stories in my mind, I foresaw the worst. A vocal argument at the least. The potential for fight, or, given the man-advantage, a beating.

I don’t hate my hometown. Despite having little interest in returning to live in Utica, New York, I enjoy my stops back to see family and friends, to eat the local delicacies, to wander through my old stomping grounds. I don’t even look back on my high school years with the sort of distaste that a lot of people as nerdy as myself might—there was a lot that I enjoyed about my school life by the time I reached my last couple years there.

But I also remember those smaller moments and bigger messages, embedded in the place where I was born and raised. The more I reflect, the more I realize, and the more I accept that I can never truly go home.

Comments

Post a Comment